Tucked in the woods here, west of State Route 520, is a little piece of the Mario Kingdom.

Tucked in the woods here, west of State Route 520, is a little piece of the Mario Kingdom.

Behind the unassuming doors is the business built by Mario, the pudgy plumber, and Luigi, his lanky brother, as well as characters like Link, wielder of the mystical Master Sword, and Princess Zelda, of the royal family of Hyrule. All of them, and more, are the pixelated children of Shigeru Miyamoto, the Walt Disney of video games and creative genius of the Nintendo Company of Japan.

But while Mr. Miyamoto is dreaming his dreams across the Pacific, an army of marketing types is at work here in Redmond, inside the shiny new headquarters of Nintendo of America. This palace of play is quiet, but there's trouble brewing in the world around it: three decades after the mustachioed Mario burst into arcades via Donkey Kong, plucking countless quarters from people's pockets, the kingdom is under siege.

Nintendo's enemies have arrived by battalions. Angry Birds, Fruit Ninja and other inexpensive, downloadable games, particularly for cellphones and tablets, have invaded its turf. Changing tastes and technology have called into question the economics of traditional game consoles, whether from Nintendo or Microsoft, maker of the Xbox. Nintendo recently posted the first loss in its era as a video games company, a prospect that would have been unimaginable only a few years ago. And while game consoles aren't going away, analysts are skeptical that the business will regain its former stature soon.

All of which makes Nintendo's next move, and what is happening here, so crucial. Nintendo counterattacked on Nov. 18, when a new version of its Wii game console arrived in stores nationwide.

The original Wii, the first wireless, motion-capturing console, was nothing less than revolutionary. The simplicity of its controller, which Mr. Miyamoto helped design, attracted new audiences like women and older people. Customers lined up in stores for it - and then it simply faded. Now, the new console, the Wii U, may be Nintendo's last, best hope for regaining its former glory. Executives are hoping for a holiday hit, and perhaps even another runaway success.Initial demand appears high. GameStop, the video game retailer, opened 3,000 stores at midnight on Thursday for Black Friday sales, and before long almost all its Wii Us were sold out, according to Tony Bartel, GameStop's president. "I think people are starving for innovation, and Wii U is giving them that innovation," Mr. Bartel says.

The Wii U is a recognition that the living room is no longer the province of a single screen. More people, particularly the young, now watch TV with a smartphone or tablet in hand, the better to tweet a touchdown or update their Facebook status during a commercial. The Wii U looks like a mash-up of an iPad and a traditional console, with a touch screen embedded in the middle. It's no mere festival of joysticks, buttons and triggers.

But will it be the blowout that Nintendo needs? Many industry veterans and game reviewers are skeptical. They question whether the Wii U can be as successful as the original, now that many gamers have moved on to more abundant, cheaper and more convenient mobile games.

"I actually am baffled by it," Nolan K. Bushnell, the founder of Atari and the godfather of the games business, says of the Wii U. "I don't think it's going to be a big success."

The bigger question is what the future holds for any of the major game systems, including new ones that Sony and Microsoft are expected to release next year. Echoing other industry veterans, Mr. Bushnell says that consoles are already delivering remarkable graphics and that few but the most hard-core players will be willing to pay hundreds of dollars for a new game box.

"These things will continue to sputter along, but I really don't think they'll be of major import ever again," he says. "It feels like the end of an era to me."

Nintendo is unbowed. Mr. Miyamoto was involved in developing the original Wii, and had a role in the Wii U as well. He rarely gives interviews, and was unavailable for comment for this article.

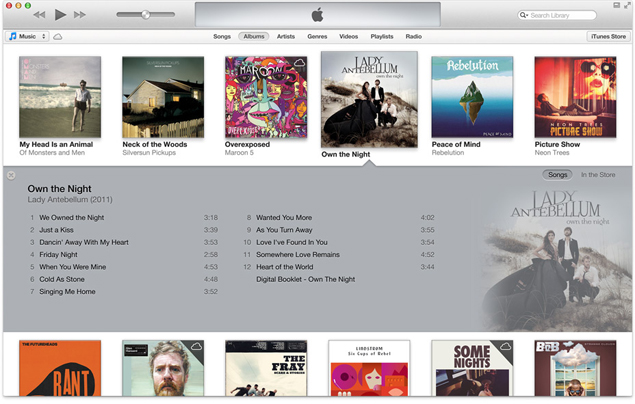

But one recent evening in Redmond, Corey Olcsvary, a Nintendo product marketing specialist, was slashing his fingers across the touch screen on the GamePad, as the Wii U controller is called, casting "throwing stars" at a ninja gang that sprang from the corners of a giant TV screen. In another game, a group of players chased Mario - one of the most popular video game characters ever - around a maze shown on a TV while Mr. Olcsvary stared at a bird's-eye view of the maze on his GamePad and tried to help Mario dodge his pursuers. The players shouted when they caught sight of Mario's red overalls and cheered when they tackled him.

Starting in December, people will also be able to use the GamePad as a remote control to set recordings and change channels on their cable and satellite TV services.

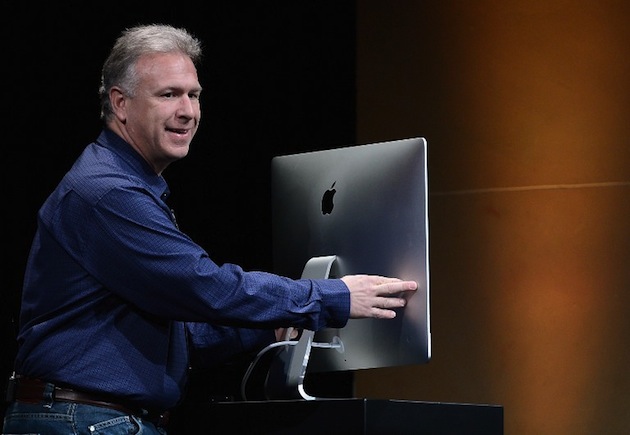

Reggie Fils-Aime, president and chief operating officer of Nintendo's United States unit, acknowledges that mobile games have changed the market. But he says wide recognition of the Nintendo and Wii brands, and of Mario, Zelda and other favorites available exclusively on Nintendo systems, will offer a strong tail wind for the Wii U.

"It comes down to providing consumers new, unique experiences they can't get anywhere else, experiences that really make them say, 'Wow, this is fantastic,' " Mr. Fils-Aime says.

Nintendo has been in the business of fun since 1889. Its founder, Fusajiro Yamauchi, made playing cards. His great-grandson Hiroshi Yamauchi landed a licensing agreement with the Walt Disney Company and turned out Mickey Mouse playing cards. By the 1960s, Nintendo was pushing into other toys and games. Then, in 1975, Atari introduced a home version of Pong, the first hit video arcade game. Soon, Nintendo was chasing video games as the hot new thing, too.

But the history of games hardware is littered with spectacular flameouts, including Sega, 3DO and Mr. Bushnell's own Atari. Nintendo has endured through a combination of ingenuity and obsessive focus on both hardware and software, a path that makes it something like the Apple of video games.

Its gutsiest bet on the hardware side was the Wii, which came out at a time when it looked as if Nintendo was drifting to the margins. Nintendo couldn't afford to join in the arms race, led by its much bigger rivals Sony and Microsoft, to create systems with the most graphics horsepower. (Years after its rivals, Nintendo has finally embraced high-definition graphics with the Wii U.)

The Wii strategy led to a big comeback. Nintendo has shipped close to 100 million Wiis, while Sony and Microsoft have each shipped about 70 million of their latest consoles.

Through it all, Mr. Miyamoto, now 60, was the creative force. But in the last year, he has let some lieutenants take on more responsibility, the better to prepare Nintendo for his eventual retirement. Mr. Fils-Aime, who would not predict when that day would be, says Mr. Miyamoto's engagement at the company "continues to be at the highest level."

Just as Apple has insisted on making both hardware and software, rather than licensing the Mac and iPhone operating systems to others, Nintendo does not create games for devices made by other companies, including the hundreds of millions of iPod Touches, smartphones and tablets out there. Industry executives say this represents a missed opportunity, allowing a new generation of game brands, like Angry Birds, to emerge unchallenged on mobile devices, much as Disney did in another realm years ago by allowing Pixar to own computer animation. (Disney later bought Pixar.)

"It's the hardest strategic decision Nintendo has had to face in a long time," says Robbie Bach, the former head of Microsoft's Xbox business. "Would Mario on an iPhone be an interesting property? I think yes, it would."

Mr. Fils-Aime says that won't happen, arguing that Nintendo's approach is the best way for it to create unique games. "That's the business decision we've made," he says, though he adds that the company may allow people to buy its games through mobile phones and have them delivered to their Nintendo devices.

While it's not unusual for sales of a particular game console to sag over time, the decline for Nintendo products in recent years has been especially brutal. The company lost 43.2 billion yen, or about $530 million, in the fiscal year ended March 31, after sharply reducing the price of a new portable game console, the Nintendo 3DS, in an effort to bolster sales. (Results were also hurt by a strong yen.) Its revenue was about a third of what it was three years earlier, when sales of the Wii and a portable device, the Nintendo DS, were booming.

"That was a magical moment," says John Taylor, an analyst at Arcadia Investment, referring to Nintendo's high point a few years ago. "The market has now moved on from that. I don't think people view an integrated tablet within the Nintendo ecosystem as nearly as impactful."

Another worrisome trend for Nintendo is that the old way of pricing and selling games seems broken. In a rocky economy, it's harder to persuade people to spend $50 to $60 - what titles typically cost for Nintendo, Sony and Microsoft systems - to buy a game. The Wii U itself starts at $300, versus $250 for the original Wii.

Cellphones and tablets have given people a nearly bottomless supply of games that typically cost a few dollars at most. Web and Facebook games are usually free, with the option to buy, say, a faster car or another virtual item that enhances the game. Industry veterans argue that you get what you pay for: mobile and Facebook games that are shallow entertainment experiences, compared with those of console games.

Mobile games are also instantly accessible online - and while it takes seconds to start a game on a smartphone or tablet, it can take minutes to get a console up and running after turning on all of the relevant equipment.

Mobile games have hurt sales of dedicated portable game devices from Nintendo and Sony, but analysts and game executives say they don't think the threat stops there.Mitch Lasky, a veteran industry executive and now a venture capitalist at Benchmark Capital, says he has walked into his living room, which is brimming with all the major game consoles, a library of new titles and a 60-inch plasma TV, only to find his children crowded around an iPhone playing Temple Run, an app-powered game available free.

"They were very much more interested in the immediacy of the mobile experience," says Mr. Lasky, who has funded several online games companies. "I'm looking at the $60 game the way I am a big-budget Hollywood movie. Yeah, I'm buying three or four a year - Call of Duty, Uncharted - but for the equivalent of television, I'm going to mobile platforms and free-to-play."

Mr. Fils-Aime says game developers can offer free games for the Wii U that generate revenue through the sale of virtual items. Sony, too, is allowing that approach with games for the PlayStation 3, and it is expected that Microsoft will more seriously embrace it as well.

It's likely that Nintendo will eventually face a more direct challenge in the living room from the same technology companies that have reshaped the mobile games business. Amazon, Apple and Google are all strong contenders to be in that camp, given their innovation track records. None have yet developed direct console competitors that have serious game-playing capabilities.

Still, Nintendo has overcome the odds before. Mr. Bach, the Microsoft ex-executive, says he doesn't underestimate the company. "I've learned not to count the Nintendo guys out," he says.